American frontiersman and politician Davy Crockett was born in 1786 in eastern Tennessee. His father, having little means, hired him out to more prosperous backwoods farmers and Davy's schooling amounted to 100 days of tutoring with a neighbor. Successive moves west to middle Tennessee brought him close to the area of the Creek War in which he made a name for himself from 1813 to 1815. In 1821 he was elected to the Tennessee legislature, winning popularity through campaign speeches filled with yarns and homespun metaphors. In the legislature an opposing speaker referred to Crockett as the “gentleman from the cane,” an allusion to the dense canebrakes of western Tennessee where Davy hunted bears and raccoons during the winter. This image of the rough backwoods legislator caught the popular imagination during Crockett's lifetime and continued to do so after his death. Following a second term in the state legislature in 1823, Crockett ran for the U.S. House of Representatives. He lost in 1825, won in 1827 and 1829, lost in 1831, barely won in 1833 and suffered his final defeat in 1835, owing to the concentrated opposition of the party of Andrew Jackson. During his first congressional term, Crockett broke with Andrew Jackson and the new Democratic party over Crockett's desire for preferential treatment of the squatters occupying land in western Tennessee. The Whigs early courted and publicized Crockett in the hope of creating a popular “coonskin” politician to offset Jackson. In 1834 Crockett was conducted on a triumphal speechmaking tour of Whig strongholds in the East. From the many stories appearing in newspapers and books during his congressional years, the legend rapidly grew of an eccentric but shrewd bear-hunting and Indian-fighting frontiersman. Actually, Crockett engaged in several business ventures and delivered his speeches in fairly conventional English. A series of Crockett almanacs, appearing from 1835 to 1856, developed the legend along the lines of Old World folk epics. Crockett's autobiography, written in 1834 with Thomas Chilton, U.S. Representative from Kentucky, played up the backwoods scene and said little about politics. It helped introduce a new style of vigorous, realistic writing into American literature. Following his 1835 defeat for Congress, Davy Crockett headed west to Texas, joined the American forces, and died along with the entire garrison of the Alamo when it was overrun by the Mexican army under General Santa Anna on March 6, 1836.

American frontiersman and politician Davy Crockett was born in 1786 in eastern Tennessee. His father, having little means, hired him out to more prosperous backwoods farmers and Davy's schooling amounted to 100 days of tutoring with a neighbor. Successive moves west to middle Tennessee brought him close to the area of the Creek War in which he made a name for himself from 1813 to 1815. In 1821 he was elected to the Tennessee legislature, winning popularity through campaign speeches filled with yarns and homespun metaphors. In the legislature an opposing speaker referred to Crockett as the “gentleman from the cane,” an allusion to the dense canebrakes of western Tennessee where Davy hunted bears and raccoons during the winter. This image of the rough backwoods legislator caught the popular imagination during Crockett's lifetime and continued to do so after his death. Following a second term in the state legislature in 1823, Crockett ran for the U.S. House of Representatives. He lost in 1825, won in 1827 and 1829, lost in 1831, barely won in 1833 and suffered his final defeat in 1835, owing to the concentrated opposition of the party of Andrew Jackson. During his first congressional term, Crockett broke with Andrew Jackson and the new Democratic party over Crockett's desire for preferential treatment of the squatters occupying land in western Tennessee. The Whigs early courted and publicized Crockett in the hope of creating a popular “coonskin” politician to offset Jackson. In 1834 Crockett was conducted on a triumphal speechmaking tour of Whig strongholds in the East. From the many stories appearing in newspapers and books during his congressional years, the legend rapidly grew of an eccentric but shrewd bear-hunting and Indian-fighting frontiersman. Actually, Crockett engaged in several business ventures and delivered his speeches in fairly conventional English. A series of Crockett almanacs, appearing from 1835 to 1856, developed the legend along the lines of Old World folk epics. Crockett's autobiography, written in 1834 with Thomas Chilton, U.S. Representative from Kentucky, played up the backwoods scene and said little about politics. It helped introduce a new style of vigorous, realistic writing into American literature. Following his 1835 defeat for Congress, Davy Crockett headed west to Texas, joined the American forces, and died along with the entire garrison of the Alamo when it was overrun by the Mexican army under General Santa Anna on March 6, 1836.

Daniel Boone was an American pioneer, soldier, and explorer. Boone was born in Pennsylvania in 1734. A frontiersman and folk hero, Boone explored the Kentucky wilderness from 1769 to 1782. He traveled down the Ohio River and trapped furs in the Green and Cumberland Valleys. He founded the first US settlement west of the Appalachian mountains. In 1773, Boone brought a group of settlers to Kentucky. As they traveled over the Cumberland Gap, Boone's oldest son, James, and five other members of the party were killed by Native Americans. The settlers went home to North Carolina immediately; Boone and his family spent the winter in the Clinch River Valley then returned home. Determined to settle the rich land of Kentucky, Judge Henderson, a wealthy local businessman, organized the Transylvania Company in order to buy land from Native Americans. Boone negotiated the price with the Cherokee Indians; their agreement is called the Watauga Treaty. In 1775, Henderson sent Boone and 28 settlers across the Cumberland Gap into Kentucky, along what is now called the Wilderness Trail. Boone built a fort on the Kentucky River in what is now Madison County. Boone was captured by Shawnee Indians in 1778 and was given up for dead. After more attacks by Native Americans, he brought more settlers to Kentucky in 1779; among these settlers were Abraham Lincoln's grandmother and grandfather. Boone was elected to the Virginia legislature in 1781. In later Indian attacks, his brother Edward and his son Israel were killed. These attacks prompted a major campaign against Native Americans by George Rogers Clark. Boone lost all of his land claims and spent the rest of his life moving - he lived in Ohio, West Virginia, and Missouri. Boone's book "Adventures" detailing his exploits and capture by the Shawnee Indians was published in 1784 to much public acclaim. He died of natural causes in 1820 on his farm near St. Louis, Missouri.

Daniel Boone was an American pioneer, soldier, and explorer. Boone was born in Pennsylvania in 1734. A frontiersman and folk hero, Boone explored the Kentucky wilderness from 1769 to 1782. He traveled down the Ohio River and trapped furs in the Green and Cumberland Valleys. He founded the first US settlement west of the Appalachian mountains. In 1773, Boone brought a group of settlers to Kentucky. As they traveled over the Cumberland Gap, Boone's oldest son, James, and five other members of the party were killed by Native Americans. The settlers went home to North Carolina immediately; Boone and his family spent the winter in the Clinch River Valley then returned home. Determined to settle the rich land of Kentucky, Judge Henderson, a wealthy local businessman, organized the Transylvania Company in order to buy land from Native Americans. Boone negotiated the price with the Cherokee Indians; their agreement is called the Watauga Treaty. In 1775, Henderson sent Boone and 28 settlers across the Cumberland Gap into Kentucky, along what is now called the Wilderness Trail. Boone built a fort on the Kentucky River in what is now Madison County. Boone was captured by Shawnee Indians in 1778 and was given up for dead. After more attacks by Native Americans, he brought more settlers to Kentucky in 1779; among these settlers were Abraham Lincoln's grandmother and grandfather. Boone was elected to the Virginia legislature in 1781. In later Indian attacks, his brother Edward and his son Israel were killed. These attacks prompted a major campaign against Native Americans by George Rogers Clark. Boone lost all of his land claims and spent the rest of his life moving - he lived in Ohio, West Virginia, and Missouri. Boone's book "Adventures" detailing his exploits and capture by the Shawnee Indians was published in 1784 to much public acclaim. He died of natural causes in 1820 on his farm near St. Louis, Missouri.

Ambrose Bierce was born in Meigs County, Ohio, in 1842. He was a printer's apprentice but influenced by his uncle, Lucius Bierce, became a strong opponent of slavery. At the outbreak of the Civil War, Lucius Bierce organized and equipped two companies of Marines. Ambrose Bierce joined one of these on April 19, 1861, and two months later became part of the invasion force led by General George McClellan in West Virginia. On April 6, 1862, Albert S. Johnson and Pierre T. Beauregard and 55,000 members of the Confederate Army attacked Grant's army near Shiloh Church in Tennessee. Taken by surprise, Grant's army suffered heavy losses. Bierce was a member of the force led by General Don Carlos Buell that forced the Confederates to retreat. Bierce was deeply shocked by what he saw at Shiloh and after the war wrote several short stories based on this experience. Bierce was promoted to the rank of second lieutenant in November 1862. Two months later he fought at Murfreesboro where he saved the life of his commanding officer, Major Braden, by carrying him to safety after he had been seriously wounded in the fighting. In February 1862 Bierce was commissioned first lieutenant of Company C of the Ninth Indiana. He fought at Chickamuga in September 1863 under General William Hazen. The sight of so many senior officers, including William Rosecrans, fleeing from the battlefield, deeply shocked Bierce. Bierce served under General William Sherman during his Atlanta Campaign. At Resaca on May 14, 1864, Bierce's close friend, Lieutenant Brayle was killed. Two weeks later his regiment suffered heavy losses when attacked by General Joseph Johnson at Pickett's Mill. Bierce was badly wounded at Kennesaw Mountain when he was shot in the head by a musket ball on June 23. After the war Bierce went to California where he became a journalist working for the Overland Monthly. He traveled to England in 1872 and worked for humorous magazines in London such as Figaro and Fun. Bierce returned to the United States in 1875 and over the next twelve years he contributed to a wide variety of different journals. In March, 1887, William Randolph Hearst, recruited Bierce to write a regular humorous article for his San Francisco Examiner. The articles were a great success and Hearst was soon paying Bierce $100 a week to retain his services. In 1891 he published a book of short-stories about the Civil War, Tales of Soldiers and Civilians (later revised and republished as In the Midst of Life). Bierce followed this with Can Such Things Be? (1893), Fantastic Fables (1899) and Shapes of Clay (1903). In 1906 Bierce published The Cynic's Word Book (reissued in 1911 as The Devil's Dictionary). As well as working for the San Francisco Examiner, Bierce contributed to journals such as Cosmopolitan, Everybody's, Hampton's Magazine and Pearson's. In 1895 he helped William Randolph Hearst with his campaign against the the railway magnate, Collis Huntington. It is argued that Bierce's articles helped to prevent the growth of Huntington's company, Southern Pacific. Bierce worked from 1909 to 1912 editing his 12 volume Collected Works. In 1913, Bierce traveled to Mexico to gain a firsthand perspective on that country's ongoing revolution. While traveling with rebel troops, the elderly writer disappeared without a trace. It is not known exactly when or how he died but it has been suggested he was killed during the siege of Ojinaga in January 1914. No trace of his body has ever been found.

Ambrose Bierce was born in Meigs County, Ohio, in 1842. He was a printer's apprentice but influenced by his uncle, Lucius Bierce, became a strong opponent of slavery. At the outbreak of the Civil War, Lucius Bierce organized and equipped two companies of Marines. Ambrose Bierce joined one of these on April 19, 1861, and two months later became part of the invasion force led by General George McClellan in West Virginia. On April 6, 1862, Albert S. Johnson and Pierre T. Beauregard and 55,000 members of the Confederate Army attacked Grant's army near Shiloh Church in Tennessee. Taken by surprise, Grant's army suffered heavy losses. Bierce was a member of the force led by General Don Carlos Buell that forced the Confederates to retreat. Bierce was deeply shocked by what he saw at Shiloh and after the war wrote several short stories based on this experience. Bierce was promoted to the rank of second lieutenant in November 1862. Two months later he fought at Murfreesboro where he saved the life of his commanding officer, Major Braden, by carrying him to safety after he had been seriously wounded in the fighting. In February 1862 Bierce was commissioned first lieutenant of Company C of the Ninth Indiana. He fought at Chickamuga in September 1863 under General William Hazen. The sight of so many senior officers, including William Rosecrans, fleeing from the battlefield, deeply shocked Bierce. Bierce served under General William Sherman during his Atlanta Campaign. At Resaca on May 14, 1864, Bierce's close friend, Lieutenant Brayle was killed. Two weeks later his regiment suffered heavy losses when attacked by General Joseph Johnson at Pickett's Mill. Bierce was badly wounded at Kennesaw Mountain when he was shot in the head by a musket ball on June 23. After the war Bierce went to California where he became a journalist working for the Overland Monthly. He traveled to England in 1872 and worked for humorous magazines in London such as Figaro and Fun. Bierce returned to the United States in 1875 and over the next twelve years he contributed to a wide variety of different journals. In March, 1887, William Randolph Hearst, recruited Bierce to write a regular humorous article for his San Francisco Examiner. The articles were a great success and Hearst was soon paying Bierce $100 a week to retain his services. In 1891 he published a book of short-stories about the Civil War, Tales of Soldiers and Civilians (later revised and republished as In the Midst of Life). Bierce followed this with Can Such Things Be? (1893), Fantastic Fables (1899) and Shapes of Clay (1903). In 1906 Bierce published The Cynic's Word Book (reissued in 1911 as The Devil's Dictionary). As well as working for the San Francisco Examiner, Bierce contributed to journals such as Cosmopolitan, Everybody's, Hampton's Magazine and Pearson's. In 1895 he helped William Randolph Hearst with his campaign against the the railway magnate, Collis Huntington. It is argued that Bierce's articles helped to prevent the growth of Huntington's company, Southern Pacific. Bierce worked from 1909 to 1912 editing his 12 volume Collected Works. In 1913, Bierce traveled to Mexico to gain a firsthand perspective on that country's ongoing revolution. While traveling with rebel troops, the elderly writer disappeared without a trace. It is not known exactly when or how he died but it has been suggested he was killed during the siege of Ojinaga in January 1914. No trace of his body has ever been found.

Julius Rosenberg was born in New York City in 1918. He attended the Hebrew High School and the City College of New York where he graduated in 1939 with a degree in electrical engineering. Later that year he married Ethel Greenglass, a clerical worker and an active trade unionist. During the Second World War Rosenberg was employed as a civilian inspector for the Army Signal Corps but was dismissed in 1945 as a result of allegations that he was a member of the American Communist Party. Rosenberg then opened a small machine shop in Manhattan with his brother-in-law, David Greenglass. However, the business did badly and Greenglass left the partnership. On September 5, 1945, Igor Gouzenko, a KGB intelligence officer based in Canada, defected to the West claiming he had evidence of an Soviet spy ring based in Britain. Gouzenko provided evidence that led to the arrest of 22 local agents and 15 Soviet spies in Canada. Some of this information from Gouzenko resulted in Klaus Fuchs being interviewed by MI5. In 1950 Fuchs, head of the physics department of the British nuclear research center at Harwell, was arrested and charged with espionage. Fuchs confessed that he had been passing information to the Soviet Union since working on the Manhattan Project during the Second World War. However, after repeated interviews with Jim Skardon he eventually confessed on January 23, 1950 to passing information to the Soviet Union. Six weeks later Fuchs was sentenced to 14 years in prison. The FBI was desperate to discover the names of the spies who had worked with Klaus Fuchs while he had been in America. Elizabeth Bentley, a former member of the American Communist Party, had, in 1945, given FBI agents eighty names of people she believed were involved in espionage. At the time it had been impossible to acquire enough information to bring the suspects to court. These people were interviewed again and one of them, Harry Gold, confessed that he had acted as Fuchs's courier. He also named David Greenglass as being a member of the spy ring. In July 1950, Greenglass was arrested by the FBI and accused of spying for the Soviet Union. Under questioning, he admitted acting as a spy and named Julius Rosenberg as one of his contacts. He denied that his sister, Ethel Rosenberg, had been involved but confessed that his wife, Ruth Greenglass, had been used as a courier. Julius Rosenberg was arrested but refused to implicate anybody else in spying for the Soviet Union. Joseph McCarthy had just launched his attack on a so-called group of communists based in Washington. The head of the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover, saw the arrest of Rosenberg as a means of getting good publicity for the FBI. Hoover sent a memorandum to the US attorney general Howard McGrath saying: "There is no question that if Julius Rosenberg would furnish details of his extensive espionage activities it would be possible to proceed against other individuals. Proceeding against his wife might serve as a lever in these matters."

Julius Rosenberg was born in New York City in 1918. He attended the Hebrew High School and the City College of New York where he graduated in 1939 with a degree in electrical engineering. Later that year he married Ethel Greenglass, a clerical worker and an active trade unionist. During the Second World War Rosenberg was employed as a civilian inspector for the Army Signal Corps but was dismissed in 1945 as a result of allegations that he was a member of the American Communist Party. Rosenberg then opened a small machine shop in Manhattan with his brother-in-law, David Greenglass. However, the business did badly and Greenglass left the partnership. On September 5, 1945, Igor Gouzenko, a KGB intelligence officer based in Canada, defected to the West claiming he had evidence of an Soviet spy ring based in Britain. Gouzenko provided evidence that led to the arrest of 22 local agents and 15 Soviet spies in Canada. Some of this information from Gouzenko resulted in Klaus Fuchs being interviewed by MI5. In 1950 Fuchs, head of the physics department of the British nuclear research center at Harwell, was arrested and charged with espionage. Fuchs confessed that he had been passing information to the Soviet Union since working on the Manhattan Project during the Second World War. However, after repeated interviews with Jim Skardon he eventually confessed on January 23, 1950 to passing information to the Soviet Union. Six weeks later Fuchs was sentenced to 14 years in prison. The FBI was desperate to discover the names of the spies who had worked with Klaus Fuchs while he had been in America. Elizabeth Bentley, a former member of the American Communist Party, had, in 1945, given FBI agents eighty names of people she believed were involved in espionage. At the time it had been impossible to acquire enough information to bring the suspects to court. These people were interviewed again and one of them, Harry Gold, confessed that he had acted as Fuchs's courier. He also named David Greenglass as being a member of the spy ring. In July 1950, Greenglass was arrested by the FBI and accused of spying for the Soviet Union. Under questioning, he admitted acting as a spy and named Julius Rosenberg as one of his contacts. He denied that his sister, Ethel Rosenberg, had been involved but confessed that his wife, Ruth Greenglass, had been used as a courier. Julius Rosenberg was arrested but refused to implicate anybody else in spying for the Soviet Union. Joseph McCarthy had just launched his attack on a so-called group of communists based in Washington. The head of the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover, saw the arrest of Rosenberg as a means of getting good publicity for the FBI. Hoover sent a memorandum to the US attorney general Howard McGrath saying: "There is no question that if Julius Rosenberg would furnish details of his extensive espionage activities it would be possible to proceed against other individuals. Proceeding against his wife might serve as a lever in these matters."

Hoover ordered the arrest of Ethel Rosenberg and her two children, Michael Rosenberg and Robert Rosenberg, were looked after by her mother, Tessie Greenglass. Julius and Ethel were put under pressure to incriminate others involved in the spy ring. Neither offered any further information. Ten days before the start of the the Rosenbergs' trial the FBI re-interviewed David Greenglass. He was offered a deal if he provided information against Ethel Rosenberg. This included a promise not to charge Ruth Greenglass with being a member of the spy ring. Greenglass now changed his story. In his original statement, he said that he handed over atomic information to Julius Rosenberg on a street corner in New York. In his new interview, Greenglass claimed that the handover had taken place in the living room of the Rosenberg's New York flat. In her FBI interview Ruth argued that "Julius then took the info into the bathroom and read it, and when he came out he told Ethel she had to type this info immediately. Ethel then sat down at the typewriter... and proceeded to type info which David had given to Julius". The trial of Julius Rosenberg and Ethel Rosenberg began on March 6, 1951. David Greenglass was questioned by the chief prosecutor assistant, Roy Cohn. After Greenglass testified to his passing sketches of a high explosive lens mold he provided incriminating detail of the Rosenberg's espionage activity. Ruth Greenglass testified as to how she was asked by Julius Rosenberg to inquire of her husband, recently stationed in Los Alamos, whether he would be willing to provide information on the progress of the Manhattan Project. She also testified that Ethel Rosenberg spent a January evening in 1945 typing her husband's handwritten notes from Los Alamos. The Rosenberg's defense attorney, Emanuel Bloch, argued that Greenglass was lying in order to gain revenge because he blamed Rosenberg for their failed business venture and to get a lighter sentence for himself. In his summation, the chief prosecutor, Irving Saypol, declared: "This description of the atom bomb, destined for delivery to the Soviet Union, was typed up by the defendant Ethel Rosenberg that afternoon at her apartment at 10 Monroe Street. Just so had she, on countless other occasions, sat at that typewriter and struck the keys, blow by blow, against her own country in the interests of the Soviets." The jury believed the evidence of David Greenglass and Ruth Greenglass and both Julius Rosenberg and his wife Ethel were found guilty and sentenced to death. A large number of people were shocked by the severity of the sentence as they had not been found guilty of treason. In fact, they had been tried under the terms of the Espionage Act that had been passed in 1917 to deal with the American anti-war movement. Afterward it became clear that the government did not believe the Rosenbergs would be executed. J. Edgar Hoover, head of the FBI, had warned that history would not be kind to a government responsible for orphaning the couple's two young sons on such poor evidence. Rumors began to circulate that the government would be willing to spare the couple's life if they confessed and gave evidence about other American Communist Party spies. The case created a great deal of controversy in Europe where it was argued that the Rosenbergs were victims of anti-semitism and McCarthyism. Julius Rosenberg and Ethel Rosenberg remained on death row for twenty-six months. They both refused to confess and provide evidence against others and they were eventually executed on June 19, 1953. As one political commentator pointed out, they died because they refused to confess and name others.

Joanna Moorhead later reported: "From the time of their parents' arrests, and even after the execution, they (the Rosenberg's two sons) were passed from one home to another - first one grandmother looked after them, then another, then friends. For a brief spell they were even sent to a shelter. It seems hard for us to understand, but the paranoia of the McCarthy era was such that many people - even family members - were terrified of being connected with the Rosenberg children, and many people who might have cared for them were too afraid to do so." Abe Meeropol and his wife eventually agreed to adopt Michael Rosenberg and Robert Rosenberg. According to Robert: "Abel didn't get any work as a writer throughout most of the 1950s... I can't say he was blacklisted, but it definitely looks as though he was at least greylisted." In December 2001, Sam Roberts, a New York Times reporter, traced David Greenglass, who was living under an assumed name with his wife, Ruth Greenglass. Interviewed on television under a heavy disguise, he acknowledged that his and his wife's court statements had been untrue. "Julius asked me to write up some stuff, which I did, and then he had it typed. I don't know who typed it, frankly. And to this day I can't even remember that the typing took place. But somebody typed it. Now I'm not sure who it was and I don't even think it was done while we were there."

David Greenglass said he had no regrets about his testimony that resulted in the execution of Ethel Rosenberg. "As a spy who turned his family in, I don't care. I sleep very well. I would not sacrifice my wife and my children for my sister... You know, I seldom use the word sister anymore; I've just wiped it out of my mind. My wife put her in it. So what am I going to do, call my wife a liar? My wife is my wife... My wife says, 'Look, we're still alive'."

In the 19th century, Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania, became an important source of anthracite coal. Most of the men who worked in these mines were immigrants from Wales, England, Germany, and Ireland. In 1868 John Siney, an Irish immigrant who had been working in coal-mines in England, formed the Workingmen's Benevolent Association. The conditions in the mines were horrendous and the men had to endure accidents, floods, fires and explosions. In one seven year period in Schuylkill County, 566 miners were killed and a further 1,665 were seriously injured. Siney's main objective was to attempt to improve pay and working conditions. John Siney was a moderate trade unionist who believed in negotiating with the employers and strictly forbade the use of violence by his members. The Workingmen's Benevolent Association threated strike action and after a short dispute the coal-mine owners agreed a small wage increase. Part of the deal involved Siney promising that he would not allow miners who used or advocated violence to remain a member of the union. Franklin B. Gowen, president of the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad, was unhappy about the increasing power of the WBA. Gowen's company owned a large number of coal-mines of Schuylkill County and feared that the activities of the WBA would reduce profits. In 1873 Gowen approached Allan Pinkerton of the Pinkerton Detective Agency about how best to destroy the union. Pinkerton decided to send Irish immigrant James McParland to Schuylkill County. Assuming the alias of James McKenna, he found work as a laborer in Shenandoah. Soon afterward he joined the Workingmen's Benevolent Association and the Shenandoah branch of the Ancient Order of Hibernians, an organization for Irish immigrants. After a few months of investigations McParland reported back to Pinkerton that some members of the Ancient Order of Hibernians were also active in the secret organization, the Molly Maguires. McParland estimated that the group had about 3,000 members. Each county was governed by a body-master who recruited members and gave out orders to commit crimes. These body-masters were usually ex-miners who now worked as saloon keepers. Over a two year period McParland collected evidence about the criminal activities of the Molly Maguires. This included the murder of around fifty men in Schuylkill County. Many of these men were the managers of coal mines in the region. John Kehoe, one of the leaders of the Molly Maguires, became suspicious of McParland and began to investigate his past. McParland was tipped off that Kehoe was planning to murder him so he fled from the area. In 1876 and 1877 McParland was the star witness for the prosecution of John Kehoe and the Molly Maguires. Twenty members were found guilty of murder and were executed. This included Kehoe, a former union activist who was convicted of a murder that had taken place fourteen years previously. There was a great deal of controversy about about the way the trial was conducted. Irish Catholics were excluded from the juries while immigrants who could not speak English were accepted. Welsh immigrants, who had for a long-time been in conflict with the Irish in Schuylkill County were also well represented on these juries. Most of the witnesses who provided evidence in these cases were, like McParland, on the payroll of the railroad and mining companies who were attempting to destroy the trade union movement. In other cases, defendants were persuaded to turn state's evidence to help convict their alleged collaborators. It was also pointed out that most of the murder victims were employees of small coal companies that were later taken over by the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad Company. Some historians have suggested that it was the company run by Franklin B. Gowen and the man who initiated the original investigation that had the most to gain from these murders and the destruction of the emerging trade union movement. In 1883 Gowen left his post as president of the company and returned to his private law practice. Gowen appeared to be doing well but on December 13, 1889, he locked himself into his hotel room and committed suicide by shooting himself in the head. After a long campaign, Joseph Wayne, John Kehoe's great grandson, managed to persuade Pennsylvania Governor Milton Shapp to grant John Kehoe, a posthumous pardon in 1980.

In the 19th century, Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania, became an important source of anthracite coal. Most of the men who worked in these mines were immigrants from Wales, England, Germany, and Ireland. In 1868 John Siney, an Irish immigrant who had been working in coal-mines in England, formed the Workingmen's Benevolent Association. The conditions in the mines were horrendous and the men had to endure accidents, floods, fires and explosions. In one seven year period in Schuylkill County, 566 miners were killed and a further 1,665 were seriously injured. Siney's main objective was to attempt to improve pay and working conditions. John Siney was a moderate trade unionist who believed in negotiating with the employers and strictly forbade the use of violence by his members. The Workingmen's Benevolent Association threated strike action and after a short dispute the coal-mine owners agreed a small wage increase. Part of the deal involved Siney promising that he would not allow miners who used or advocated violence to remain a member of the union. Franklin B. Gowen, president of the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad, was unhappy about the increasing power of the WBA. Gowen's company owned a large number of coal-mines of Schuylkill County and feared that the activities of the WBA would reduce profits. In 1873 Gowen approached Allan Pinkerton of the Pinkerton Detective Agency about how best to destroy the union. Pinkerton decided to send Irish immigrant James McParland to Schuylkill County. Assuming the alias of James McKenna, he found work as a laborer in Shenandoah. Soon afterward he joined the Workingmen's Benevolent Association and the Shenandoah branch of the Ancient Order of Hibernians, an organization for Irish immigrants. After a few months of investigations McParland reported back to Pinkerton that some members of the Ancient Order of Hibernians were also active in the secret organization, the Molly Maguires. McParland estimated that the group had about 3,000 members. Each county was governed by a body-master who recruited members and gave out orders to commit crimes. These body-masters were usually ex-miners who now worked as saloon keepers. Over a two year period McParland collected evidence about the criminal activities of the Molly Maguires. This included the murder of around fifty men in Schuylkill County. Many of these men were the managers of coal mines in the region. John Kehoe, one of the leaders of the Molly Maguires, became suspicious of McParland and began to investigate his past. McParland was tipped off that Kehoe was planning to murder him so he fled from the area. In 1876 and 1877 McParland was the star witness for the prosecution of John Kehoe and the Molly Maguires. Twenty members were found guilty of murder and were executed. This included Kehoe, a former union activist who was convicted of a murder that had taken place fourteen years previously. There was a great deal of controversy about about the way the trial was conducted. Irish Catholics were excluded from the juries while immigrants who could not speak English were accepted. Welsh immigrants, who had for a long-time been in conflict with the Irish in Schuylkill County were also well represented on these juries. Most of the witnesses who provided evidence in these cases were, like McParland, on the payroll of the railroad and mining companies who were attempting to destroy the trade union movement. In other cases, defendants were persuaded to turn state's evidence to help convict their alleged collaborators. It was also pointed out that most of the murder victims were employees of small coal companies that were later taken over by the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad Company. Some historians have suggested that it was the company run by Franklin B. Gowen and the man who initiated the original investigation that had the most to gain from these murders and the destruction of the emerging trade union movement. In 1883 Gowen left his post as president of the company and returned to his private law practice. Gowen appeared to be doing well but on December 13, 1889, he locked himself into his hotel room and committed suicide by shooting himself in the head. After a long campaign, Joseph Wayne, John Kehoe's great grandson, managed to persuade Pennsylvania Governor Milton Shapp to grant John Kehoe, a posthumous pardon in 1980.

Texas Jack was a frontier scout, actor, and cowboy. He was born John B. Omohundro in Palmyra, Virginia, in 1846. In his early teens, he left home, made his way alone to Texas, and became a cowboy. Unable to join the Confederate Army in 1861 because of his youth, he entered Confederate service as a courier and scout. In 1864, he enlisted in Gen. J.E.B. Stuart's command as a courier and scout. Shortly after the Civil War Omohundro adopted a five year old boy whose parents had been killed by Native Americans. He cared for him and called him Texas Jack Jr., since his real last name was unknown. In 1869, he moved to Cottonwood Springs, Nebraska, near Fort McPherson and became a scout and buffalo hunter. There he met William F. "Buffalo Bill" Cody. Together, they participated in Indian skirmishes and buffalo hunts, acted as guides for notables such as the Earl of Dunraven, and led the highly publicized royal hunt of 1872 with Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich of Russia and a group of prominent American military figures. Texas Jack and Buffalo Bill traveled to Chicago in December 1872 to debut in "The Scouts of the Prairie", one of the original Wild West shows produced by Ned Buntline. Critics described Omohundro as physically impressive and magnetic in personality. He was the first performer to introduce roping acts to the American stage. During the 1873-74 season, Omohundro and Cody invited their friend Wild Bill Hickok to join them in a new play called "Scouts of the Plains." During the 1870s, Texas Jack divided his time between the Eastern stage circuit and the hunting ranges of the Great Plains. He guided hunting parties that included European nobility. On August 31, 1873, Omohundro married Giuseppina Morlacchi, a dancer and actress from Milan, Italy, who starred with him in the "Scouts of the Prairie" and other shows. He headed his own acting troupe in St. Louis in 1877. He also wrote articles about his hunting and scouting experiences, published in eastern newspapers and popular magazines. The Texas Jack legend grew in many dime novels, particularly those written by Col. Prentiss Ingraham. In 1900, Joel Chandler Harris featured Texas Jack in a series of fictional accounts of the Confederacy for the Saturday Evening Post. Texas Jack died of pneumonia in 1880 in Leadville, Colorado, and was buried in Evergreen Cemetery there. Texas Jack, Jr. carried on in the wild west show business around the world, especially in South Africa.

Texas Jack was a frontier scout, actor, and cowboy. He was born John B. Omohundro in Palmyra, Virginia, in 1846. In his early teens, he left home, made his way alone to Texas, and became a cowboy. Unable to join the Confederate Army in 1861 because of his youth, he entered Confederate service as a courier and scout. In 1864, he enlisted in Gen. J.E.B. Stuart's command as a courier and scout. Shortly after the Civil War Omohundro adopted a five year old boy whose parents had been killed by Native Americans. He cared for him and called him Texas Jack Jr., since his real last name was unknown. In 1869, he moved to Cottonwood Springs, Nebraska, near Fort McPherson and became a scout and buffalo hunter. There he met William F. "Buffalo Bill" Cody. Together, they participated in Indian skirmishes and buffalo hunts, acted as guides for notables such as the Earl of Dunraven, and led the highly publicized royal hunt of 1872 with Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich of Russia and a group of prominent American military figures. Texas Jack and Buffalo Bill traveled to Chicago in December 1872 to debut in "The Scouts of the Prairie", one of the original Wild West shows produced by Ned Buntline. Critics described Omohundro as physically impressive and magnetic in personality. He was the first performer to introduce roping acts to the American stage. During the 1873-74 season, Omohundro and Cody invited their friend Wild Bill Hickok to join them in a new play called "Scouts of the Plains." During the 1870s, Texas Jack divided his time between the Eastern stage circuit and the hunting ranges of the Great Plains. He guided hunting parties that included European nobility. On August 31, 1873, Omohundro married Giuseppina Morlacchi, a dancer and actress from Milan, Italy, who starred with him in the "Scouts of the Prairie" and other shows. He headed his own acting troupe in St. Louis in 1877. He also wrote articles about his hunting and scouting experiences, published in eastern newspapers and popular magazines. The Texas Jack legend grew in many dime novels, particularly those written by Col. Prentiss Ingraham. In 1900, Joel Chandler Harris featured Texas Jack in a series of fictional accounts of the Confederacy for the Saturday Evening Post. Texas Jack died of pneumonia in 1880 in Leadville, Colorado, and was buried in Evergreen Cemetery there. Texas Jack, Jr. carried on in the wild west show business around the world, especially in South Africa. Left to right: Ned Buntline, Bufalo Bill Cody, Giuseppina Morlacchi, Texas Jack Omohundro

Left to right: Ned Buntline, Bufalo Bill Cody, Giuseppina Morlacchi, Texas Jack Omohundro

William Quantrill joined the Confederate Army on the outbreak of the American Civil War. He fought at Lexington but disliked the regimentation of army life and decided to form a band of guerrilla fighters. As well as attacking Union troops Quantrill Raiders also robbed mail coaches, murdered supporters of Abraham Lincoln, and persecuted communities in Missouri and Kansas that Quantrill considered to be anti-Confederate. He also gained a reputation for murdering members of the Union Army that the gang had taken prisoner. In 1862, Quantrill and his men were formally declared to be outlaws. By 1863 Quantrill was the leader of over 450 men, including Frank James, Jessie James, Cole Younger, and James Younger. With this large force he committed one of the worst atrocities of the Civil War when he attacked the town of Lawrence, Kansas. During the raid on August 21, 1863, Quantrill's gang killed 150 residents of the town and destroyed over 180 buildings. The district Union commander, General Thomas Ewing, was furious when he heard what the Quantill Raiders had done. On August 25 he issued Order No 11 which gave an eviction notice to all people in the area who could not prove their loyalty to the Union cause. Ewing's decree virtually wiped out the entire region. The population of Cass County dropped from 10,000 to 600. Quantrill found it difficult to keep his men under control as they tended to go off and commit their own crimes. By 1865 he had only 33 followers left. On May 10, 1865, Quantrill was ambushed by federal troops. He died from his wounds on June 6, 1865. Many of the group continued under the leadership of Archie Clement, who kept the Raiders together after the war and harassed the state government of Missouri during the tumultuous year of 1866. In December 1866, state militiamen killed Clement in Lexington, Missouri, but his men continued on as outlaws, emerging in time as the James-Younger Gang.

William Quantrill joined the Confederate Army on the outbreak of the American Civil War. He fought at Lexington but disliked the regimentation of army life and decided to form a band of guerrilla fighters. As well as attacking Union troops Quantrill Raiders also robbed mail coaches, murdered supporters of Abraham Lincoln, and persecuted communities in Missouri and Kansas that Quantrill considered to be anti-Confederate. He also gained a reputation for murdering members of the Union Army that the gang had taken prisoner. In 1862, Quantrill and his men were formally declared to be outlaws. By 1863 Quantrill was the leader of over 450 men, including Frank James, Jessie James, Cole Younger, and James Younger. With this large force he committed one of the worst atrocities of the Civil War when he attacked the town of Lawrence, Kansas. During the raid on August 21, 1863, Quantrill's gang killed 150 residents of the town and destroyed over 180 buildings. The district Union commander, General Thomas Ewing, was furious when he heard what the Quantill Raiders had done. On August 25 he issued Order No 11 which gave an eviction notice to all people in the area who could not prove their loyalty to the Union cause. Ewing's decree virtually wiped out the entire region. The population of Cass County dropped from 10,000 to 600. Quantrill found it difficult to keep his men under control as they tended to go off and commit their own crimes. By 1865 he had only 33 followers left. On May 10, 1865, Quantrill was ambushed by federal troops. He died from his wounds on June 6, 1865. Many of the group continued under the leadership of Archie Clement, who kept the Raiders together after the war and harassed the state government of Missouri during the tumultuous year of 1866. In December 1866, state militiamen killed Clement in Lexington, Missouri, but his men continued on as outlaws, emerging in time as the James-Younger Gang. Reunion of Quantrill's Raiders, 1920

Reunion of Quantrill's Raiders, 1920

Salmon Portland Chase was born in New Hampshire in 1808. After his father died in 1817, he lived with his uncle, Philander Chase, the Bishop of Ohio. After graduating from Dartmouth College in 1826 he worked briefly as a school teacher in Washington. In 1830 Chase moved to Cincinnati where he established himself as a lawyer. A member of the Anti-Slavery Society, Chase defended so many re-captured slaves he became known as the "attorney general for runaway negroes". He also provided free legal advice for those caught working for the Underground Railroad. Chase was originally a member of the Whig Party but joined the Liberty Party in 1841. However, in August 1848, Chase and other members of the party joined with anti-slavery members of the Whig Party to form the Free-Soil Party. The following year Chase was elected to the United States Senate. Together with Joshua Giddings, Chase was seen as the leader of the anti-slavery group in Congress and played an important role in the campaign against the Kansas-Nebraska Act. In 1855 Chase was elected as the governor of Ohio. A founding member of the Republican Party, he sought the party presidential nomination in 1860 but on the third ballot asked his supporters to vote for Abraham Lincoln. When Lincoln became president, Chas was appointed as Lincoln's Secretary of the Treasury and had responsibility for organizing the finance of the Union war effort. He also helped to establish a national banking system. Chase was the most progressive member of Lincoln's Cabinet and shared many of the views being expressed by the Radical Republican group. He constantly clashed with the more conservative William Seward and on several occasions came close to resigning. Chase was highly critical of those officers in the Union Army such as Irvin McDowell, George McClellan and Henry Halleck who appeared unwilling to attack the Confederate Army in 1862. He himself wanted the war to be a crusade against slavery and told Lincoln: "Proslavery sentiment inspires rebellion, let anti-slavery sentiment inspire suppression." In the summer of 1862 Chase and Abraham Lincoln clashed over the treatment of General David Hunter. In May, Hunter began enlisting black soldiers in the occupied districts of South Carolina and soon afterward issued a statement that all slaves owned by Confederates in the area were free. Lincoln was furious and instructed him to disband the 1st South Carolina (African Descent) regiment and to retract his proclamation. Chase agreed with Hunter's actions and once again came close to resigning. The main argument that Chase had with Lincoln was that the president refused to state that emancipation of the slaves was an object of the war. In Cabinet meetings Chase was the only member to argue for black suffrage. Chase eventually resigned in June 1864. Lincoln wrote a letter accepting Chase's resignation agreeing that their relationship had "reached a point of mutual embarrassment that could not be overcome". In December 1864, Abraham Lincoln appointed Chase as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Like other Radical Republican, Chase was highly critical of Lincoln's Reconstruction Plans. He was even more critical of those followed by Andrew Johnson and as Chief Justice presided over the Senate impeachment proceedings against Andrew Johnson. Over the next few years Chase interpreted the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution in ways that helped to protect the rights of blacks from infringement by state action. Salmon P. Chase died in 1873 in New York City and is interred in Spring Grove Cemetery in Cincinnati.

Salmon Portland Chase was born in New Hampshire in 1808. After his father died in 1817, he lived with his uncle, Philander Chase, the Bishop of Ohio. After graduating from Dartmouth College in 1826 he worked briefly as a school teacher in Washington. In 1830 Chase moved to Cincinnati where he established himself as a lawyer. A member of the Anti-Slavery Society, Chase defended so many re-captured slaves he became known as the "attorney general for runaway negroes". He also provided free legal advice for those caught working for the Underground Railroad. Chase was originally a member of the Whig Party but joined the Liberty Party in 1841. However, in August 1848, Chase and other members of the party joined with anti-slavery members of the Whig Party to form the Free-Soil Party. The following year Chase was elected to the United States Senate. Together with Joshua Giddings, Chase was seen as the leader of the anti-slavery group in Congress and played an important role in the campaign against the Kansas-Nebraska Act. In 1855 Chase was elected as the governor of Ohio. A founding member of the Republican Party, he sought the party presidential nomination in 1860 but on the third ballot asked his supporters to vote for Abraham Lincoln. When Lincoln became president, Chas was appointed as Lincoln's Secretary of the Treasury and had responsibility for organizing the finance of the Union war effort. He also helped to establish a national banking system. Chase was the most progressive member of Lincoln's Cabinet and shared many of the views being expressed by the Radical Republican group. He constantly clashed with the more conservative William Seward and on several occasions came close to resigning. Chase was highly critical of those officers in the Union Army such as Irvin McDowell, George McClellan and Henry Halleck who appeared unwilling to attack the Confederate Army in 1862. He himself wanted the war to be a crusade against slavery and told Lincoln: "Proslavery sentiment inspires rebellion, let anti-slavery sentiment inspire suppression." In the summer of 1862 Chase and Abraham Lincoln clashed over the treatment of General David Hunter. In May, Hunter began enlisting black soldiers in the occupied districts of South Carolina and soon afterward issued a statement that all slaves owned by Confederates in the area were free. Lincoln was furious and instructed him to disband the 1st South Carolina (African Descent) regiment and to retract his proclamation. Chase agreed with Hunter's actions and once again came close to resigning. The main argument that Chase had with Lincoln was that the president refused to state that emancipation of the slaves was an object of the war. In Cabinet meetings Chase was the only member to argue for black suffrage. Chase eventually resigned in June 1864. Lincoln wrote a letter accepting Chase's resignation agreeing that their relationship had "reached a point of mutual embarrassment that could not be overcome". In December 1864, Abraham Lincoln appointed Chase as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Like other Radical Republican, Chase was highly critical of Lincoln's Reconstruction Plans. He was even more critical of those followed by Andrew Johnson and as Chief Justice presided over the Senate impeachment proceedings against Andrew Johnson. Over the next few years Chase interpreted the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution in ways that helped to protect the rights of blacks from infringement by state action. Salmon P. Chase died in 1873 in New York City and is interred in Spring Grove Cemetery in Cincinnati.

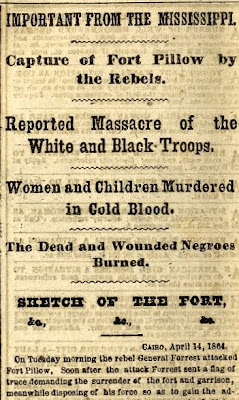

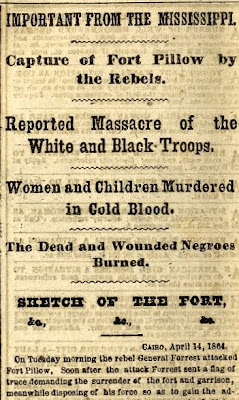

The Fort Pillow massacre was one of the worst blots on the record of Confederate troops during the American Civil War. Fort Pillow was located on the Tennessee bank of the Mississippi River and had fallen into Union hands in May 1862. However, even two years later, and with the main fighting now focused on the road to Atlanta, Confederate raiders still forced the Union to maintain garrisons across the occupied south. One of the best known of those raiders was General Nathan Bedford Forrest. He had been commanding the cavalry of the army in Tennessee but after the Confederate victory at Chickamauga in September 1864, he had fallen out with General Bragg and refused to serve under him any longer. While Bragg settled down to besiege Chattanooga, Forrest headed back to an independent command in Mississippi. In March 1864, Forrest took a division of cavalry (about 1,500 men) on a raid north through western Tennessee that actually reached as far north as Paducah, Kentucky. It was on his way back south that Forrest and his men committed what is now generally accepted as a massacre. Fort Pillow was garrisoned by one regiment of black troops, numbering 262, and a cavalry detachment of similar size, for a total of 557 men. On April 12, 1864, Forrest’s men attacked the fort. After a brief fight they overwhelmed the garrison. Confederate losses were fairly low (14 killed and 86 wounded). Union losses were much heavier. Of the garrison of 557 men, 231 were killed, 100 wounded and 226 captured. Only 75 of the 262 black troops were amongst the captured. The very high number of dead immediately attracted attention. The Federal commander of the fort, Major William Bradford, was conveniently killed "while attempting to escape". Despite southern denials at the time, it seems clear that several dozen black soldiers were killed after they had surrendered. Fort Pillow was the most visible outbreak of a Confederate fury at the very idea of black soldiers. The Fort Pillow massacre and a suitable response to it was the subject of some days debate in Lincoln’s cabinet. In the end, they could not find a response that would not risk escalating beyond control. Meanwhile, black soldiers continued to play a major, and increasing, role in the Union war effort, providing nearly 200,000 men to the northern war effort. After the war an official investigation discovered evidence that "the Confederates were guilty of atrocities which included murdering most of the garrison after it surrendered, burying Negro soldiers alive, and setting fire to tents containing Federal wounded." However, Nathan Bedford Forrest was never prosecuted for the offense and he went on to become the first Imperial Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan.

The Fort Pillow massacre was one of the worst blots on the record of Confederate troops during the American Civil War. Fort Pillow was located on the Tennessee bank of the Mississippi River and had fallen into Union hands in May 1862. However, even two years later, and with the main fighting now focused on the road to Atlanta, Confederate raiders still forced the Union to maintain garrisons across the occupied south. One of the best known of those raiders was General Nathan Bedford Forrest. He had been commanding the cavalry of the army in Tennessee but after the Confederate victory at Chickamauga in September 1864, he had fallen out with General Bragg and refused to serve under him any longer. While Bragg settled down to besiege Chattanooga, Forrest headed back to an independent command in Mississippi. In March 1864, Forrest took a division of cavalry (about 1,500 men) on a raid north through western Tennessee that actually reached as far north as Paducah, Kentucky. It was on his way back south that Forrest and his men committed what is now generally accepted as a massacre. Fort Pillow was garrisoned by one regiment of black troops, numbering 262, and a cavalry detachment of similar size, for a total of 557 men. On April 12, 1864, Forrest’s men attacked the fort. After a brief fight they overwhelmed the garrison. Confederate losses were fairly low (14 killed and 86 wounded). Union losses were much heavier. Of the garrison of 557 men, 231 were killed, 100 wounded and 226 captured. Only 75 of the 262 black troops were amongst the captured. The very high number of dead immediately attracted attention. The Federal commander of the fort, Major William Bradford, was conveniently killed "while attempting to escape". Despite southern denials at the time, it seems clear that several dozen black soldiers were killed after they had surrendered. Fort Pillow was the most visible outbreak of a Confederate fury at the very idea of black soldiers. The Fort Pillow massacre and a suitable response to it was the subject of some days debate in Lincoln’s cabinet. In the end, they could not find a response that would not risk escalating beyond control. Meanwhile, black soldiers continued to play a major, and increasing, role in the Union war effort, providing nearly 200,000 men to the northern war effort. After the war an official investigation discovered evidence that "the Confederates were guilty of atrocities which included murdering most of the garrison after it surrendered, burying Negro soldiers alive, and setting fire to tents containing Federal wounded." However, Nathan Bedford Forrest was never prosecuted for the offense and he went on to become the first Imperial Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan.

Thurgood Marshall was born in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1908. His father was a steward in a white social club and his mother was a school teacher. Marshall was a brilliant student and received degrees from Lincoln University in 1930 and Howard University Law School in 1933. Charles Houston was one of Marshall's tutors at Howard University and in 1936 he advised Walter Francis White, executive director of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP), to appoint Marshall to the organization's legal department. The two men now began the NAACP's campaign against segregation in transportation and publicly owned places of recreation, inequities in the segregated education system, and restrictive covenants in housing. In 1939 Marshall became director of the NAACP's Legal Defense and Educational Fund. Over the next few years Marshall won 29 of the 32 cases that he argued before the Supreme Court. President John F. Kennedy nominated Marshall to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit on September 23, 1961 but opposition from Southern senators delayed the appointment until September 11, 1962. In July 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed Marshall as his U.S. solicitor general. Two years later Marshall became the first African American to join the Supreme Court. For over twenty years Thurgood Marshall was a consistent supporter of individual rights. His views often clashed with Richard Nixon and in 1987 he controversially told a television interviewer that Ronald Reagan had the worst presidential record on civil rights since Woodrow Wilson. Republican appointments to the Supreme Court eventually left Marshall an isolated liberal in an increasingly conservative body. He resigned on June 27, 1991, after writing a strong statement against a conservative majority decision in Payne v Tennessee. Thurgood Marshall died at Bethesda, Maryland, on January 24, 1993.

Thurgood Marshall was born in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1908. His father was a steward in a white social club and his mother was a school teacher. Marshall was a brilliant student and received degrees from Lincoln University in 1930 and Howard University Law School in 1933. Charles Houston was one of Marshall's tutors at Howard University and in 1936 he advised Walter Francis White, executive director of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP), to appoint Marshall to the organization's legal department. The two men now began the NAACP's campaign against segregation in transportation and publicly owned places of recreation, inequities in the segregated education system, and restrictive covenants in housing. In 1939 Marshall became director of the NAACP's Legal Defense and Educational Fund. Over the next few years Marshall won 29 of the 32 cases that he argued before the Supreme Court. President John F. Kennedy nominated Marshall to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit on September 23, 1961 but opposition from Southern senators delayed the appointment until September 11, 1962. In July 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed Marshall as his U.S. solicitor general. Two years later Marshall became the first African American to join the Supreme Court. For over twenty years Thurgood Marshall was a consistent supporter of individual rights. His views often clashed with Richard Nixon and in 1987 he controversially told a television interviewer that Ronald Reagan had the worst presidential record on civil rights since Woodrow Wilson. Republican appointments to the Supreme Court eventually left Marshall an isolated liberal in an increasingly conservative body. He resigned on June 27, 1991, after writing a strong statement against a conservative majority decision in Payne v Tennessee. Thurgood Marshall died at Bethesda, Maryland, on January 24, 1993.

By the standards of his day, David Wilmot could be considered a racist. Yet the U.S. Representative from Pennsylvania was so adamantly against the extension of slavery to lands ceded by Mexico he made a proposition that would divide the Congress. On August 8, 1846, Wilmot introduced legislation in the House that boldly declared, "neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall ever exist" in lands won in the Mexican-American War. If he was not opposed to slavery, why would Wilmot propose such an action? Why would the North, which only contained a small, but growing minority, of abolitionists, agree? Wilmot and other northerners were angered by President James K. Polk. They felt that the entire Cabinet and national agenda were dominated by southern minds and southern principles. Polk was willing to fight for southern territory but proved willing to compromise when it came to the North. Polk had lowered the tariff and denied funds for internal improvements, both to the dismay of northerners. Now they felt a war was being fought to extend the southern way of life. The term "Slave Power" jumped off the lips of northern lawmakers when they angrily referred to their southern colleagues. It was time for northerners to be heard. Though Wilmot's heart did not bleed for the slave, he envisioned California as a place where free white Pennsylvanians could work without the competition of slave labor. Since the North was more populous and had more Representatives in the House, the Wilmot Proviso passed. Laws require the approval of both houses of Congress, however. The Senate, equally divided between free states and slave states could not muster the majority necessary for approval. Angrily the House passed Wilmot's Proviso several times, all to no avail. It would never become law.

By the standards of his day, David Wilmot could be considered a racist. Yet the U.S. Representative from Pennsylvania was so adamantly against the extension of slavery to lands ceded by Mexico he made a proposition that would divide the Congress. On August 8, 1846, Wilmot introduced legislation in the House that boldly declared, "neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall ever exist" in lands won in the Mexican-American War. If he was not opposed to slavery, why would Wilmot propose such an action? Why would the North, which only contained a small, but growing minority, of abolitionists, agree? Wilmot and other northerners were angered by President James K. Polk. They felt that the entire Cabinet and national agenda were dominated by southern minds and southern principles. Polk was willing to fight for southern territory but proved willing to compromise when it came to the North. Polk had lowered the tariff and denied funds for internal improvements, both to the dismay of northerners. Now they felt a war was being fought to extend the southern way of life. The term "Slave Power" jumped off the lips of northern lawmakers when they angrily referred to their southern colleagues. It was time for northerners to be heard. Though Wilmot's heart did not bleed for the slave, he envisioned California as a place where free white Pennsylvanians could work without the competition of slave labor. Since the North was more populous and had more Representatives in the House, the Wilmot Proviso passed. Laws require the approval of both houses of Congress, however. The Senate, equally divided between free states and slave states could not muster the majority necessary for approval. Angrily the House passed Wilmot's Proviso several times, all to no avail. It would never become law.